Nestled in the southwestern stretch of Nawalparasi (West) in Lumbini Province, Nepal, Ramgram Municipality has steadily transformed from a traditionally agricultural community into a thriving urban-industrial hub. With its eastern boundary touching Palhinandan Rural Municipality, western front connected to Sarawal, northern edge meeting Bardaghat, and southern border brushing Susta and the Indian frontier, Ramgram’s geography places it at a key crossroads of trade, migration, and development. Spanning an area of 91.69 square kilometers and accommodating a total population of over 69,476 (as per the 2021 census), this municipality is a reflection of Nepal’s rural-urban transition. Farmers still till the land for rice, wheat, maize, and sugarcane, while industries—such as flour mills, distilleries, concrete block factories, and paper production units—have sprouted rapidly in the last decade. This dual identity of farming and industrialization has brought both opportunities and challenges. As roads expand and smokestacks rise, questions have emerged about the quality of the air, the purity of water, the health of soil, and the overall livability of this fast-changing landscape. To investigate this imbalance and guide future decisions, the municipality commissioned its first comprehensive environmental monitoring study carried out during February and March 2025 in technical collaboration with Lumbini Agro Environment Lab Pvt. Ltd. The goal was simple yet essential: use science to understand, protect, and restore the environment before it’s too late.

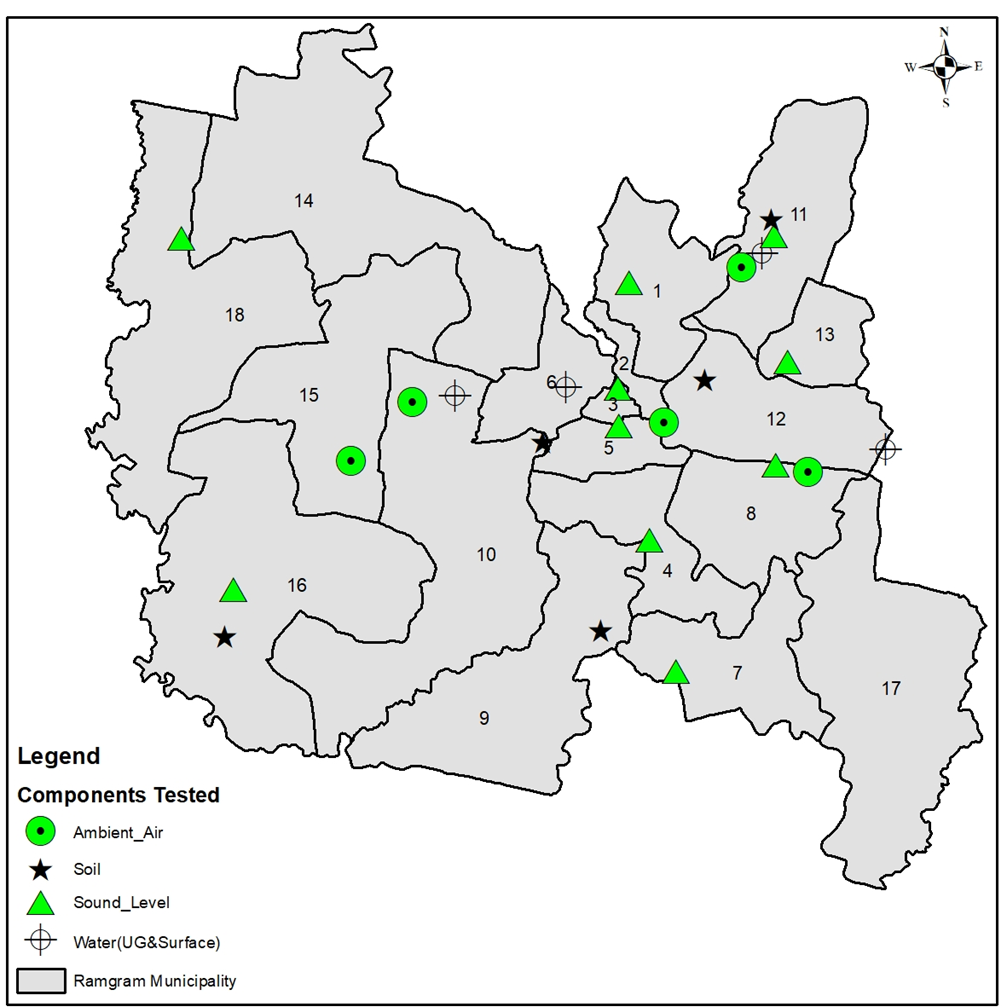

So, why was this environmental study initiated and why now? Until recently, Ramgram’s approach to environmental issues was reactive rather than strategic. Complaints about polluted air or murky wastewater were addressed on an ad-hoc basis, and there was no consistent or scientific system in place to measure environmental quality. As industries multiplied, vehicular traffic intensified, and construction projects spread across previously green fields, the effects on human health and natural resources became harder to ignore. Local residents began to report more cases of respiratory discomfort, dust accumulation, and crop yield decline. Yet these observations lacked the credibility or clarity needed for informed decision-making. Recognizing this growing concern, Ramgram Municipality in partnership with Lumbini Agro Environment Lab Pvt. Ltd. launched its first comprehensive environmental monitoring study in 2025. The goal was to establish a clear, evidence-based understanding of air, water, noise, and soil conditions across 24 strategic sites, including industrial zones, busy intersections, agricultural fields, and public institutions. What set this initiative apart was not just its scope, but its intent: to turn data into dialogue, measurement into policy, and concern into corrective action.

What did this study find and how serious is the situation today? The answer became dramatically clear in Chaitra 2081 (April 2025), when Ramgram and neighboring areas recorded an Air Quality Index (AQI) of 173, officially categorized as “Unhealthy.” According to Lumbini Agro Environment Lab, PM2.5 levels reached 82 µg/m³ and PM10 levels 91 µg/m³, far exceeding both Nepali and WHO safety standards. This spike wasn’t a coincidence. It was largely fueled by transboundary air pollution—specifically, crop residue burning in India’s Punjab region, where smoke from stubble fires is carried across the border into Nepal by prevailing winds. Scientific research published in ScienceDirect confirms that these particles often settle in Nepal’s Terai belt, including Nawalparasi. To make matters worse, forest fires erupted in the Chure range and nearby forest zones of Nawalparasi, further intensifying the presence of airborne toxins. Global air monitoring platform IQAir corroborated the rise in pollutant concentration, identifying the region as one of the worst-hit during this period. The result was a perfect storm of cross-border haze, local smoke, and stagnant atmospheric conditions, creating a significant health crisis for residents—especially vulnerable groups like children, the elderly, and people with asthma or chronic respiratory issues.

But the broader study offered more than just a snapshot of the crisis. It painted a holistic picture of Ramgram’s environmental health across four dimensions. Air quality tests using High Volume Air Samplers showed persistently high levels of PM10, PM2.5, and Total Suspended Particulates (TSP), especially near factories like Lumbini Paper Board Pvt. Ltd., where TSP reached 318 µg/m³. In terms of water quality, while drinking water samples generally passed microbial safety tests, turbidity levels in some industrial sources exceeded the safe limit of 5 NTU, and industrial wastewater samples—particularly from Aruna Distillery—recorded COD levels of 356 mg/L and BOD levels of 104 mg/L, well above national discharge limits. These numbers indicate untreated organic waste being released into local streams, affecting aquatic life and downstream users. Noise pollution, too, showed alarming figures: Bairihawa Chowk recorded over 85 dB during the day, significantly beyond the safe threshold for urban zones. Finally, soil testing revealed that while some areas like Daunne Flour Mills showed high fertility, others like Ward No. 9 exhibited acidic pH (5.6) and nutrient depletion, raising concerns about long-term agricultural sustainability. These findings established the municipality’s first environmental baseline and revealed just how interlinked industrial growth and ecological degradation have become.

So, what should Ramgram and municipalities like it do next to secure a better future? The first step, as outlined by Lumbini Agro Environment Lab, is to translate data into targeted environmental policy. For air pollution, this includes enforcing the installation of bag filters, scrubbers, and electrostatic precipitators in high-emission industries, along with promoting green belts and electric mobility to reduce vehicular emissions.

For water pollution, the report recommends mandatory, monitored Effluent Treatment Plants (ETPs) in all factories, regular wastewater audits, and incentives for water reuse and rainwater harvesting. To reduce noise exposure, particularly in sensitive zones, the municipality can develop sound zoning maps, promote low-noise machinery, and build acoustic buffers around schools and hospitals. For agriculture, the implementation of soil health cards, composting programs, and rotation with nitrogen-fixing crops is essential to restore soil fertility. Beyond technical fixes, the study stresses community engagement. Farmers must be trained in organic techniques, industries educated about sustainable production, and schoolchildren involved in environmental awareness programs. This local engagement, paired with government regulation, is the only way to build resilience that lasts.

Ultimately, what does this mean for the future of Ramgram and why does it matter beyond its borders? What’s unfolding in Ramgram is not just a local issue; it is a reflection of Nepal’s broader environmental crossroads. As the country moves toward economic modernization, towns like Ramgram offer valuable lessons on how development must be matched by ecological stewardship. The air pollution crisis of April 2025 is a stark reminder that environmental neglect has direct, measurable consequences on human health and well-being. But Ramgram’s response—rooted in science, data, and community collaboration—demonstrates what’s possible when municipalities act with foresight. This is the beginning of a longer journey: one that will require annual monitoring, policy refinement, public accountability, and youth leadership. Lumbini Agro Environment Lab remains committed to supporting this transformation—not only through testing and reporting, but through training, education, and innovation. As Ramgram embraces this new era of environmental governance, it can emerge as a model green municipality, where urban growth and nature coexist, and where science serves the future. The lessons learned here can inspire similar action across Nepal, helping ensure that our children inherit not just a more developed country—but a cleaner, safer, and more livable one.

Authors: Sudip Paudel

Co-author: Prativa Acharya